By laying numbers, words, and phrases onto otherwise abstract imagery, the late Argentinian artist prophesized the dread-inducing news alerts of our time.

Sarah Grilo, Pines, Ochres and Green (1963), oil on canvas, 44 x 50 inches (© The Estate of Sarah Grilo; image courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.)

Among the 17 paintings by artist Sarah Grilo in Galerie Lelong’s The New York Years, 1962–1970, one work most dramatically prophesizes the dread-inducing news alerts of our time. The brushwork in beiges, browns, greens, and grays in “America’s going…” (1967) is overlain by red lettering that the artist transferred from newspapers, eerily resembling those red chyrons that flash on our phones and stream across cable news today.

Born in Argentina in 1917, Grilo was creating introspective art amid social and political unrest well before she moved to New York. Through the group Artistas Modernos de la Argentina, she became an important painter amid the male-dominated Buenos Aires art scene of the 1950s, singled out for her monochromatic, geometric, and expressionistic approaches to lyrical abstraction.

After winning a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1961, Grilo and her husband, painter José Antonio Fernández-Muro, relocated to New York City. There, her approach took a decisive turn toward incorporating language into the picture planes, which would define her oeuvre for the next half-century until her death in 2007.

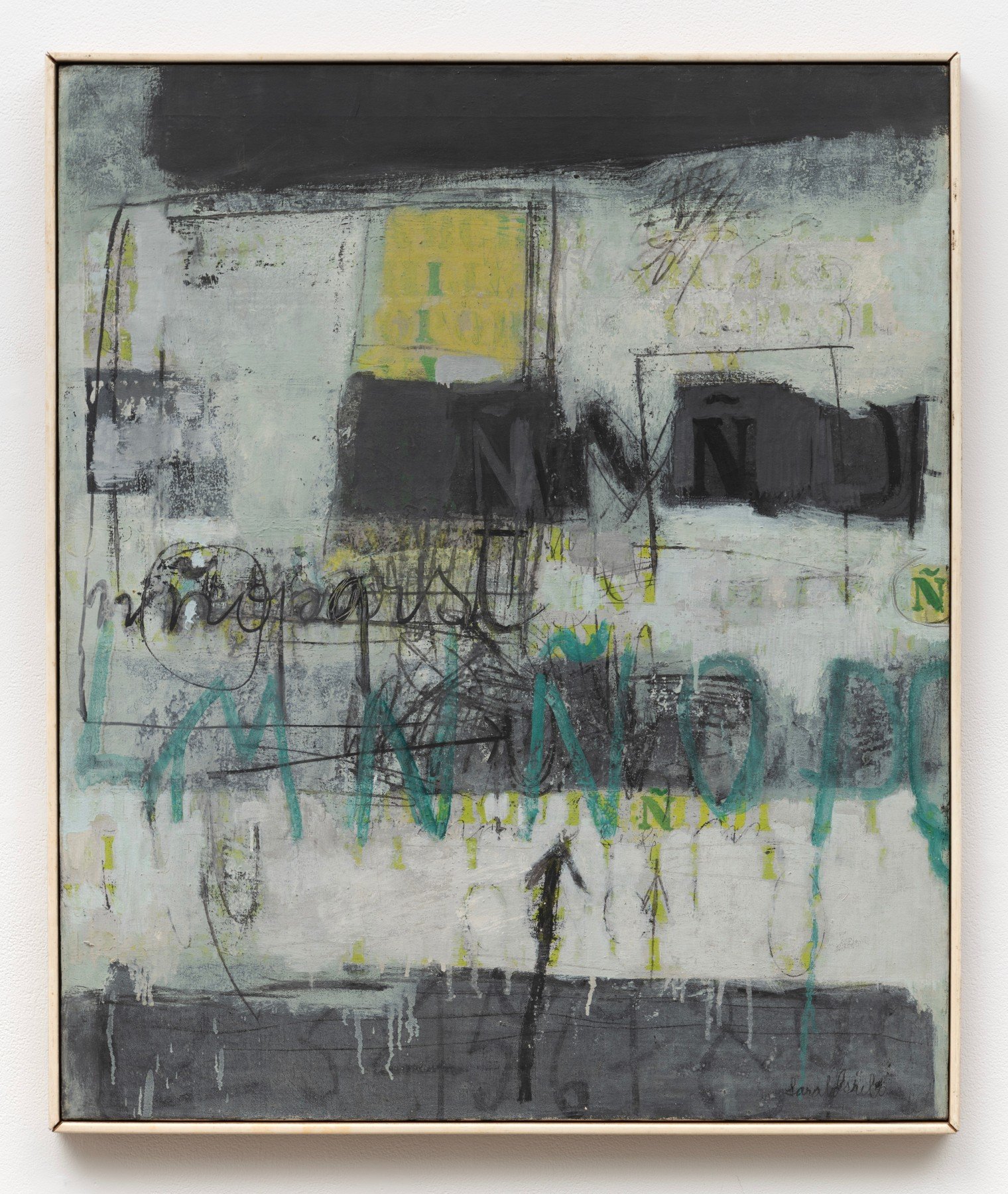

Sarah Grilo, Homage to my language (letter Ñ) (1965), oil on canvas, 32 x 26 7/8 inches (© The Estate of Sarah Grilo; image courtesy Estrellita B. Brodsky Collection)

Today, much as it did in decades past, Grilo’s work poses a puzzling question: What propelled a formerly restrained painter to introduce found text, as well as painted numerals, handwritten transcriptions, and calligraphic notes, into her canvases? This mystery is teased out through the pairing of her paintings with period photos, reviews of her work (about which critics were divided), and portraits of Grilo around the city, alongside the magazines from which she appropriated texts.

The exhibition highlights an artist opening herself up to the city’s spontaneous diversity and bringing late modernism into conversation with a postwar pop landscape. But while it may reference Andy Warhol’s co-opting of consumer products and Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines series, Grilo’s art avoids the facile cool and sardonic complicity of Pop art. Instead, she evokes an energetic American zeitgeist sinking under the weight of its many moral contradictions. In her carefully selected transfer-texts, the country’s puritanical hopefulness seems in lockstep with its cynical salesmanship. The appropriated text in “Charts are dull” (1965), for one, highlights America’s anti-intellectual zeal for unfiltered experience, though that tagline was lifted from a magazine ad for the Plymouth Belvedere sedan.

In nonverbal paintings free of text, Grilo deploys drips, impasto, and scumbling techniques to contrast subdued grayish tones with opulent colors, lending these abstractions the aura of the ancient or otherworldly. “Orange and mauve” (1963) looks like a scintillating, ultra-magnified slide from a fission experiment while “Pines Ochres and Greens” (1963) maps fertile topographical regions scarred by blackened tracts suggesting incineration.

(…)

Read more here.